The Book of Ecclesiastes says that there is nothing new under the sun. And while many have spoken of the “unprecedented” nature of the rioting in the early summer of 2020, it is actually quite precedented.

The Book of Ecclesiastes says that there is nothing new under the sun. And while many have spoken of the “unprecedented” nature of the rioting in the early summer of 2020, it is actually quite precedented.The Long, Hot Summer of 1967 was the peak of urban unrest and rioting in the United States in the lead up to the 1968 election. While there are certainly a number of key differences, there are also a number of striking parallels that make the topic worthy of discussion and examination.

The long-term impact of the urban unrest of the summer of 2020 is unclear, but the long-term impact of the Long, Hot Summer of 1967 and related urban rioting was a victory for Richard Nixon in 1968, and a landslide re-election in 1972. One must resist the temptation to make mechanistic comparisons between the two, and we will refrain from doing so here. But the reader is encouraged to look for connections between these events and more recent ones.

Prologue: The Ghetto Riots

The riot wave in America’s urban ghettos might have peaked in the summer of 1967, but it certainly didn’t begin there. 1964 is generally thought to be the beginning, with a riot that began in Harlem after the shooting of a 15-year-old black teenager named James Powell.

The story of how this happened is familiar to anyone who read the news in the summer of 2020: The superintendent of a building in a predominantly white working-class neighborhood turned a hose on black students who had been congregating on the stoops of his buildings. The black students alleged that he used racist language with them, a charge that he denied. It is worth noting how often alleged racial slurs are invoked as an excuse for violence. In any case, no one disagrees that the students then began throwing garbage can lids and bottles at him. He retreated into his building where he was pursued by three of the students, one of them being James Powell.

A white off-duty police officer, Lieutenant Thomas Gilligan, arrived on the scene and fired three shots at Powell. One of these was a warning shot, but the other two connected with Powell’s forearm and abdomen. Lieutenant Gilligan claimed that Powell had a knife, raised it and then he fired first a warning shot, then a shot into the forearm to disarm him before firing the third shot. Gilligan had an impeccable record with the New York Police Department. Powell had a few interactions with the law: twice for boarding a subway car without paying, once for breaking the window of a vehicle and once for an attempted robbery (he was cleared of the robbery).

The result was a week of rioting that left one dead, 118 injured and 465 arrested.

Between the Harlem Riot of 1964 and the Long, Hot Summer of 1967, there were riots in Rochester, New York, Dixmoor, Illinois, Philadelphia, Watts, Chicago, Cleveland, Waukegan, Illinois, San Francisco and Benton Harbor, Michigan. But the Long, Hot Summer was when things really picked up.

Chapter One: The Long, Hot Summer of 1967

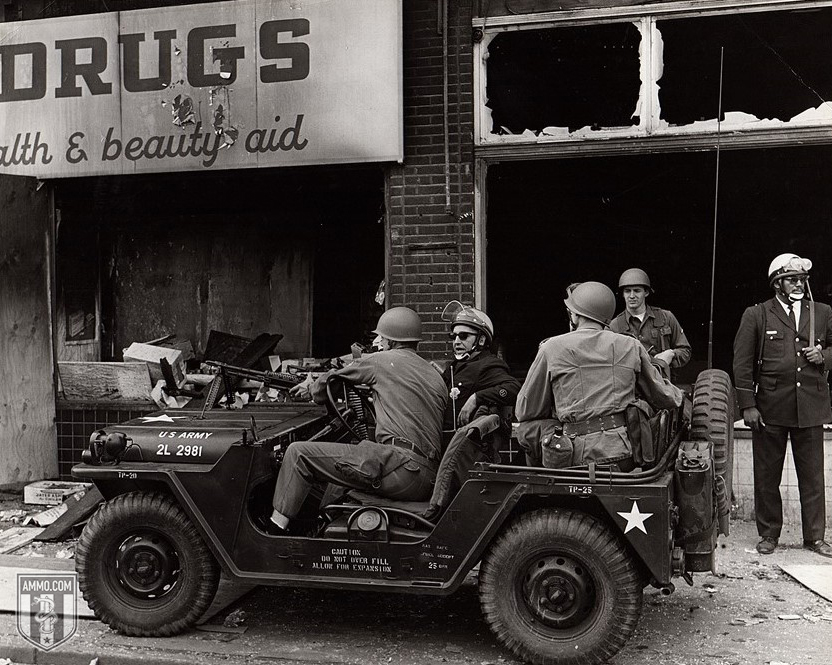

It would be impossible to cover all of the rioting that occurred throughout the summer of 1967. All told, there were 159 riots that summer. The worst of these were in Newark, New Jersey and Detroit, Michigan. The riots left over 85 dead, over 2,100 injured and over 11,000 arrested. They also caused tens of millions of dollars in property damage.

It would be impossible to cover all of the rioting that occurred throughout the summer of 1967. All told, there were 159 riots that summer. The worst of these were in Newark, New Jersey and Detroit, Michigan. The riots left over 85 dead, over 2,100 injured and over 11,000 arrested. They also caused tens of millions of dollars in property damage.

The first of these riots was the Cincinnati riot of that year, which began in the Avondale region of the city, in response to the conviction of “Cincinnati Strangler” Posteal Laskey Jr. for a series of rapes and murders. Laskey’s cousin, Peter Frakes, protested the decision and was arrested for blocking the sidewalk, in stark contrast to the protesters of today who are allowed to block off highways. The next day there was a protest in support of Frakes that spiralled out of control, quickly becoming an orgy of violence, destruction and looting that spread throughout the city.

Resulting in one death, 63 injured, 404 arrested and $2 million in property damage (over $15 million in 2020 dollars), the riot was only quelled when the National Guard was deployed.

Cincinnati was the first, but the two biggest riots were in Newark and Detroit.

Newark was one of the earliest and most extreme examples of white flight in the nation. Its manufacturing base had largely abandoned the city by the time that the riots began. The city had been on edge for a while, but things began to boil over in July 1967, after Newark white police officers John DeSimone and Vito Pontrelli beat black cab driver John William Smith, who they claimed assaulted them. A rumor began to spread that Smith was beaten to death and a crowd formed outside of the police station. Witnesses disagree as to what happened first – the crowd throwing things or the police emerging with hard hats and clubs.

The crowd demanded that Smith be moved to Beth Israel Hospital, a request granted by the police. That night there was a march to protest police brutality, during which an unidentified female smashed the windows of the police precinct with metal bars. Looting and firebombing of local businesses began soon after, with the looting of liquor stores being a predominant feature of the rioting.

Six days of rioting left 16 civilians, eight suspects, a police officer and a firefighter dead. There were 727 injuries (including 67 police officers, 55 firefighters, and 38 military personnel) and $10 million in property damage (roughly $77 million in 2020 dollars). Many believe that the city never fully recovered from the riots even to this day.

The riots in Detroit took place from July 23 to 28. At around 3:45 a.m., Detroit police broke up a party at a “blind pig” (unlicensed private drinking club). They expected to find only a few, but instead were greeted by an 82-person strong celebration of the return of two GIs from Vietnam. The police made the decision to arrest everyone there. A crowd began to gather to watch the raid. William Walter Scott III, the doorman and son of the organizer of the blind pig, later admitted to starting the riot by throwing a bottle at a police officer in his memoirs.

The next afternoon, the first fire was set at a grocery store. The local media tried simply ignoring the riots in an attempt to maintain calm. Tigers left fielder Willie Horton, who was born in Virginia but lived in and grew up in Detroit, drove to the center of the rioting and stood on his car in uniform, passionately imploring the crowd to stop the violence, but failed to do so.

Chaos began on the second day of rioting. There were 483 fires, with 231 incidents reported every hour, and a whopping 1,800 arrests in a single day. Hardy's drug store, a black-owned business known to fill prescriptions on credit, was one of the first to be burned to the ground. Indeed, the black business district was not spared. Firefighters were shot at as they attempted to put out fires. U.S. Representative John Conyers tried to address the rioters via loudspeaker out of his car, but had rocks and bottles thrown at him.

All told, there were at least 23 deaths and 696 wounded, with property damage pegged somewhere between $40 million to $45 million (between $300 and $350 million in 2020 dollars). Among those dead were 4-year-old Tanya Blanding.

The final riot in the Long, Hot Summer of 1967 was the Milwaukee riot, which left four dead, 100 injured and 1,740 arrested. This began after two police showed up to break up a fight between two black women, around which a crowd of 350 had gathered. The property damage was relatively scant because it was mostly confined to broken windows: it came in at around $200,000 at the time.

Chapter Two: The King Assassination Riots of 1968

The next wave of rioting took place following the assassination of Martin Luther King in the spring of 1968. This wave of riots engulfed the nation’s capital, Chicago, Baltimore, Kansas City, Detroit, New York, Pittsburgh, Cincinnati, Trenton, Wilmington and Louisville. New York’s riots were quickly quelled by mayor John Lindsay, who went directly to Harlem and gave a speech about addressing poverty. Sen. Robert F. Kennedy is largely credited with saving Indianopolis, with his speech there following King’s assassination. A James Brown concert in Boston is similarly credited with keeping the peace there. Memorials were held in Los Angeles that averted a repeat of the 1965 Watts riots.

Washington, D.C. was the first to experience rioting, beginning on the day of King’s assassination, April 4. Ironically, the rioting here was started by a mob following Stokely Carmichael of the Southern Nonviolent Coordinating Committee, who quickly began breaking windows. The riots devastated the black business district of the city, which had an incredibly difficult time finding investment to rebuild after the riots were over. Some areas of the city remained little more than piles of rubble until 1999.

Riots in Chicago came next, starting the day after King’s assassination. The damage here was over $10 million (over $77 million in 2020 dollars), with 11 dead, 500 injured, and 2,150 arrested. Baltimore was next, two days later. The swift and sharp response of Governor Spiro T. Agnew (thousands of National Guard and 500 Maryland State Police were deployed the very day that unrest began) was likely what attracted then-candidate Richard Nixon to choose him as his running mate.

The riots following the assassination of Martin Luther King Jr. were comparatively minor when contrasted with the Long, Hot Summer of 1967. However, it is worth noting that they happened as part of a more general pattern of lawlessness and urban unrest in the United States in the late 1960s.

It is now generally agreed that the wave of rioting in 1968 helped to sweep Richard Nixon into the White House. The riots outside of the Democratic National Conventionin 1968 likewise didn’t help matters. However, whether or not the 2020 election will be a replay of the 1968 election (which also took place during a pandemic that left over 100,000 Americans dead) remains to be seen. At the very least, the Democrats are going to spare themselves unrest by holding their convention virtually.

Epilogue: The Hard Hat Riot

For every action, there is an equal and opposite reaction. This might be a law of physics, but it often holds in politics as well. The reaction to urban rioting and leftist violence in general that plagued the late 60s and early 70s is a little-known incident in American history known as the Hard Hat Riot.

For every action, there is an equal and opposite reaction. This might be a law of physics, but it often holds in politics as well. The reaction to urban rioting and leftist violence in general that plagued the late 60s and early 70s is a little-known incident in American history known as the Hard Hat Riot.

The Hard Hat Riot took place on May 8, 1970, in New York City of all places. It’s worth remembering that in 1970, most of New York was a lot more like blue-collar forklift operator Archie Bunker of All in the Family rather than Lena Dunham – Bunker lived in Astoria, Queens, which is a much different place today than it was at the time of the Hard Hat Riot.

Unlike the hippies and college students of America, blue-collar workers tended to support Nixon and his Vietnam War policies. Peter J. Brennan, who was the head of the Building and Construction Trades Council of Greater New York, was one of the most vocal supporters of Nixon and the Vietnam War.

The Hard Hat Riot started as a counter-protest to a protest against the killing of four students at Kent State by the National Guard. It started with a few hundred college and high school students, but quickly ballooned to over 1,000. They were soon met by about 200 construction workers carrying American flags and patriotic signs. Their numbers doubled when people working in the surrounding area joined the construction workers. The construction workers began beating anyone with long hair in the vicinity of their counter-protest.

After this, the construction workers stormed city hall and raised the flag, which had been at half mast for the Kent State students, back to full mast. They were joined by city workers, including a postal worker who raised an American flag on the roof of city hall. Most of the rioters were Catholic and turned their attention to the nearby Episcopal church in the neighborhood.

Six rioters were arrested and Mayor John Lindsay denounced the rioters, as well as police for their lack of action. A massive influx of phone calls to local union offices were 20 to 1 in support of the rioters. On May 11 and May 16, there were additional protests denouncing Mayor Lindsay as a “commie” and a “rat.” It’s worth noting that “rat” is a term approximating “scab” in the building trades. On May 20, 150,000 pro-war demonstrators marched through the city without opposition. Many workers who were on the job showered the demonstration with ticker tape.

Peter J. Brennan met with Nixon and 22 other labor leaders on May 26, presenting the president with a hard hat. Brennan later met privately with the president on Labor Day. He is considered instrumental in securing a second term in the White House for President Nixon, and was rewarded for his efforts with the Secretary of Labor position.

What all of these have in common are a template for community unrest in advance of an election year. While not a direct reaction to the urban riots, the Hard Hat Riots were largely the urban white working class saying “enough” to the racialized and political violence that had plagued the country for the last several years.

While 2020 saw the merger of racialized and political violence running rampant in the early summer, it has yet to see any kind of organized – and we use that term loosely – pushback of the order of the Hard Hat Riots. Americans are a tolerant and a patient people, but their tolerance and patience has a limit. Whether or not there will be an analog to the Hard Hat Riots in the future is anyone’s guess, but if history repeats (or even, as Mark Twain once said, rhymes) we will be seeing something not unlike the Hard Hat Riots in the near future.